Was there a Gaelic settlement in Ireland?

IRISH SETTLEMENT STUDIES The landscape of Gaelic Ireland There is a growing consciousness that our discourse of the medieval settlement history of Ireland is strongly influenced by the availability of Latin sources for those settlements which were established under the Anglo-Normans.

When did early medieval Ireland settle?

Graham, B.J. (1993) ‘Early medieval Ireland: settlement as an indicator of economic and social transformation, c. 500–1100’, in B.J. Graham and L.J. Proudfoot (eds) An Historical Geography of Ireland (London), 19–57.

What are the best- documented settlements in Ireland’s history?

Undoubtedly the best-documented settlements are the twenty-five mercantile towns involved in Ireland’s external trade. These were probably characterised by a burgher class – organised in guilds – comprised of artisans, traders and merchants.

What was the principal settlement form in Ireland?

In Ireland too, the chartered settlement fulfilled this role. Consequently the borough of the fiefholder – the ‘knight of the soil’ – was the principal settlement form through which that economy operated.

What are the striking features of Neolithic archaeology in Ireland?

By contrast, one of the striking features of Neolithic archaeology in Ireland has been the regular discoveries of further Neolithic houses90 (Figure 1.5; Plate 1.1). Particularly significant discoveries in recent years have been the two houses at

What is the evidence for Neolithic settlement?

Indeed, the evidence for Neolithic settlement has significant potential for the analysis of the use and organisation of social space within and around houses. Work has continued on the most visible aspect of the Neolithic, namely megalithic tombs and other burial and ceremonial sites.107 In terms of understanding contemporary settlement, what is relevant is the specific relationship between tombs and houses and broader patterns of distribution of different kinds of tombs as a guide to the pattern of settlement. Looking at the association between houses and megalithic tombs we may be talking here again simply about differential preservation of settlement evidence in protected situations under the mounds of these tombs, but it is clear that there was also an association between the idea of the houses for the living and the dead (Plate 1.1).108 More broadly, the quantity of the tombs, now over 1,560,109 compared to the relatively small number of known settlement sites, means that in terms of looking at regional or national settlement trends the tombs have been discussed in the context of their relationship with contemporary settlement.110 That relationship would seem to be very varied, both over time and space. Most importantly in this regard has been a recognition of the need to break away from the traditional, culturalhistorical model of different types of tombs representing different, successive societies or people with different ethnic identities.111 Radiocarbon dates indicate that there was a substantial overlap in the construction and use of court, portal and passage tombs. Added to this, in distributional terms there are areas where different types occur in close proximity, as in the case of the Cooley Peninsula, Co. Louth (Figure 1.7). So we have to face the probability that in some areas different tombs were used by the same people, perhaps with different roles in mind. Looking at the complex interlocking distribution patterns, it is clear that any simple dichotomy between a society based on local territories exemplified in the building of a court tomb, and a more complex and regionally based social organisation based on the construction of passage tombs112 is an inadequate explanation, perhaps owing more to the framework of explanation current in the 1970s than to any Neolithic reality. It is clear, for example, that groupings of tombs – ‘cemeteries’ – are not just a feature of passage tombs, an assumption that had been at the core of the analytic convention of seeing the passage tombs as different from other megalithic tombs, but that groupings of other tombs also occur.113 In detailed regional studies it is clear that the position of tombs in the landscape may in some cases have been central to potential settlement zones whereas in other cases they may have been peripheral or even occurred in a distinct cemetery.114 Over time there may have been a change in the character and role of the tombs in Neolithic society, as local foci were complemented by tombs with a wider role, perhaps reflecting the increasing scale of social interaction.115 A notable feature has been the recognition of a distinctive form of burial monument, the so-called Linkardstown cists, with an emphasis on single burial.116 These are concentrated in the southern part of the island and are again contemporary with megalithic tombs. This may indicate a regional trend in south 15

What was the first major phase of trackway construction?

Longford.156 Here and elsewhere the removal through milling of the upper level of bogs has to be borne in mind, but it does appear that the Bronze Age was the first major period of trackway construction, although a small number of Neolithic trackways are known. In the first instance this may relate to increased human activity in the Irish midlands during the Bronze Age. As a specific example, the large-scale clearance seen in the pollen record round 1000 BC is matched by a peak in trackway construction. It would appear that the construction of trackways reflects periods of agricultural and settlement expansion rather than a reaction to ‘events’ of climatic deterioration.157 Evidence for the Later Bronze Age (1200–500 BC) is still dominated by metal artifacts but very significant changes in the archaeological record have taken place in recent years. The most significant is the recognition of a range of settlement sites falling into a number of categories. The dating of the trivallate hillforts at Haughey’s Fort in the Navan complex158 and at Mooghaun, Co. Clare159 to between 1200–1000 BC establishes clearly that hillforts have to be regarded as a feature of this period. Further support for this comes from the Later Bronze Age settlement activity, including a large circular house, within the multivallate hillfort at Rathgall, Co. Wicklow.160 There was Later Bronze Age activity within Navan Fort itself, in the form of a ditched enclosure with an internal structure underlying the complex sequence of Iron Age activity.161 Excavation at the multivallate cliff-edge fort at Dún Aonghasa (Plate 1.2) revealed a complex Later Bronze Age occupation with circular houses and evidence for metalworking. The occupation spans the period between 1300–800 BC.162 Both the location of these Later Bronze Age settlements and their character, for example the evidence from Haughey’s Fort for the storage of grain, perhaps gathered from a hinterland, the access to large breeds of animals and gold production,163 suggest that they are at the top of a settlement, social and economic hierarchy. In this context it seems very probable that there would have been a ceremonial or ritual aspect to activity on such sites.164 Other elements in this structure are represented by sites like that at Clonfinlough, Co. Offaly, a wetland, lakeside enclosed site defined by a timber palisade within which there were at least three circular houses with central hearths and plank floors.165 The site is dated dendrochronologically to around 900 BC. It can be compared to other sites such as Lough Eskragh, Co. Tyrone,166 Knocknalappa, Co. Clare and Rathinaun, Co. Sligo.167 Another category of wetland site can be recognised from the evidence at Moynagh Lough, Co. Meath168 and Killymoon, Co. Tyrone169 where the material seems to suggest not so much a standard residential site as a location for activities such as metal production, cereal processing and deliberate deposition that might be associated with a high-status site. Representing sites that are enclosed but not heavily protected in this settlement structure is the settlement at Curraghatoor, Co. Tipperary where there was 22

How long has the Neolithic landscape been open?

hundred years, and in some cases the landscape may have remained open right through the Neolithic.82 It has been argued that the shifting cultivation model is inappropriate for prehistoric temperate European conditions where the prevalent wide spectrum, mixed farming strategy could have provided the basis for secure long-term occupation of farmed areas.83 The most important archaeological back-up of this has been the discovery of Neolithic field systems, particularly in north-west Mayo as the result of the work of Caulfield.84 While Céide Fields (Figure 1.4) is the largest, most regular and best-known example, smaller-scale systems and stretches of field boundaries are known from other areas as far apart as Antrim,85 Donegal86 and Kerry, as for example from Valencia Island.87 In all cases these consist of boundaries protected from removal by the fossilisation of the landscape under blanket bog. This raises the issue of whether field boundaries were utilised in areas that have continued on in agricultural use and the author has argued elsewhere88 that we should assume this would frequently have been the case. By contrast, in Britain the emphasis in interpretation over the last ten years has shifted to regarding Neolithic settlement as based on mobility, with the continuing importance of the use of wild resources and bounding of the land seen as more a feature of the Bronze Age.89 There are a number of reasons for this stance but important factors are the

When was the first human settlement in Ireland?

However a bear bone found in Alice and Gwendoline Cave, County Clare, in 1903 may push back dates for the earliest human settlement of Ireland to 10,500 BC. The bone shows clear signs of cut marks with stone tools and has been radiocarbon dated to 12,500 years ago.

When was Ireland first discovered?

The first evidence of human presence in Ireland dates to around 33,000 years ago , further findings have been found dating to around 10,500 to 8,000 BC. The receding of the ice after the Younger Dryas cold phase of the Quaternary around 9700 BC, heralds the beginning of Prehistoric Ireland, which includes the archaeological periods known as the Mesolithic, the Neolithic from about 4000 BC and the Copper Age beginning around 2500 BC with the arrival of the Beaker Culture. The Irish Bronze Age proper begins around 2000 BC and ends with the arrival of the Iron Age of the Celtic Hallstatt culture, beginning about 600 BC. The subsequent La Tène culture brought new styles and practices by 300 BC.

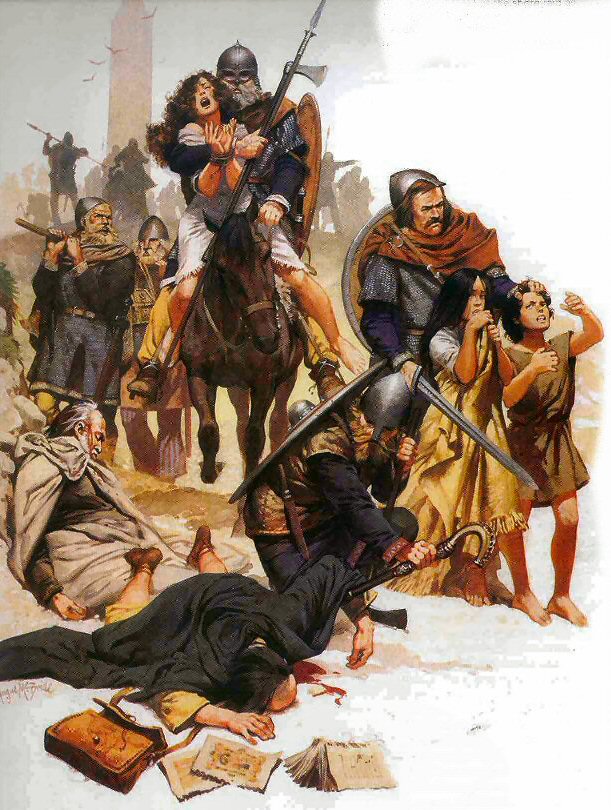

What were the changes in Ireland in the first millennium?

The middle centuries of the first millennium AD marked great changes in Ireland. Politically, what appears to have been a prehistoric emphasis on tribal affiliation had been replaced by the 8th century by patrilineal dynasties ruling the island's kingdoms. Many formerly powerful kingdoms and peoples disappeared. Irish pirates struck all over the coast of western Britain in the same way that the Vikings would later attack Ireland. Some of these founded entirely new kingdoms in Pictland and, to a lesser degree, in parts of Cornwall, Wales, and Cumbria. The Attacotti of south Leinster may even have served in the Roman military in the mid-to-late 300s.

What is known about pre-Christian Ireland?

What is known of pre-Christian Ireland comes from references in Roman writings, Irish poetry, myth, and archaeology. While some possible Paleolithic tools have been found, none of the finds is convincing of Paleolithic settlement in Ireland. However a bear bone found in Alice and Gwendoline Cave, County Clare, in 1903 may push back dates for the earliest human settlement of Ireland to 10,500 BC. The bone shows clear signs of cut marks with stone tools and has been radiocarbon dated to 12,500 years ago.

What are the four types of tombs in Ireland?

Four main types of Irish Megalithic Tombs have been identified: dolmens, court cairns, passage tombs and wedge-shaped gallery graves.

What is known about Ireland during the Ice Age?

Ireland during the Ice Age. What is known of pre-Christian Ireland comes from references in Roman writings, Irish poetry, myth, and archaeology. While some possible Paleolithic tools have been found, none of the finds is convincing of Paleolithic settlement in Ireland.

When did Rome conquer Ireland?

The closest Rome got to conquering Ireland was in 80 AD.